Abel doesn’t shy away from the darker parts of his story. He tells them the way they happened, raw and unpolished, because that’s the truth.

He was born in Liberia during a civil war. His mother immigrated to Canada first, before bringing him over. When he was not yet three years old, Abel made that journey alone. He doesn’t remember the trip itself. What he knows comes from what others have told him: that he stayed with immigration services for a short time before being reunited with his mother a couple of weeks later.

But safety didn’t follow.

As a little boy, Abel would sometimes be found wandering the streets at night, alone, until police picked him up and brought him home. He moved between relatives’ houses, never settling long enough to feel rooted anywhere. At school, teachers noticed he often arrived dirty or late. By the age of ten, he was permanently placed in foster care.

His first foster home lasted three months. In his second, he cried himself to sleep for weeks. “I’d stay up all night, apparently crying for weeks on end,” he remembers. That placement ended after a month.

Much of his childhood is a blur. “It’s like a slide show… like still frames,” Abel says. He pieces together the gaps from old photographs or from what others have told him.

What he does know is this: those early years carved deep scars. The constant moving. The losses. The violence. They left him with a fear of abandonment so strong it would shape much of what came after.

Statistics tell the same story over and over again. Children who endure unstable homes, abuse, or time in foster care are far more likely to end up in the justice system or struggling with addiction.1 Abel fits that pattern. He recalls his grandfather as a “disciplinarian,” but others would call it what it was: child abuse. In Canada, half of incarcerated men report being neglected or abused as children.2

Abel kept in contact with his mom, but she often broke promises, and made no attempt to get him back when she had the chance. “She’s my mom. She gave birth to me. But I never had that maternal feeling of safety, love and trust.”

By almost every measure, Abel was failed by family and by the adults who were supposed to protect him.

And yet, there were moments of light. One foster home lasted eight years. The woman who cared for him there is still in his life today. In a childhood full of chaos, she was one of the few steady things.

Addiction

Addiction doesn’t happen overnight. It’s a gradual process shaped by early trauma, mental health challenges, and exposure to addictive substances over time. Abel checked many of those boxes. As a child, he was diagnosed with ADHD and struggled with clinical depression and generalized anxiety disorder, conditions that often overlap with substance use.3 Life was so lonely at times that he attempted suicide on three separate occasions.

He was introduced to drugs at 17 by a foster brother.

“Substances were never in my life prior to this,” Abel says. “I think I was living in that innocence. I wasn’t socially adept; I wouldn’t pick up on social cues… I was just so unaware.”

So when his foster brother offered him marijuana, Abel tried it.

What might look like a choice from the outside is often the result of how trauma rewires the brain. Trauma in childhood weakens decision-making, makes stress harder to manage, and leaves fewer tools for healthy coping.4

Abel liked the way he felt when he was high. “I was laughing, acting silly, getting attention. It felt great.” For someone who always wanted to fit in, that feeling was powerful. “It wasn’t just a recreational drug for me. It was a way to fit in. It took away all the anxiety and stuff. I didn’t feel anything.”

Things escalated when Abel turned 18 and was moved out of foster care. “I didn’t really look for work, didn’t really have groceries. All I cared about was my weed.”

New friends introduced him to ecstasy, meth, cocaine, and eventually crack. Each step pulled him further in.

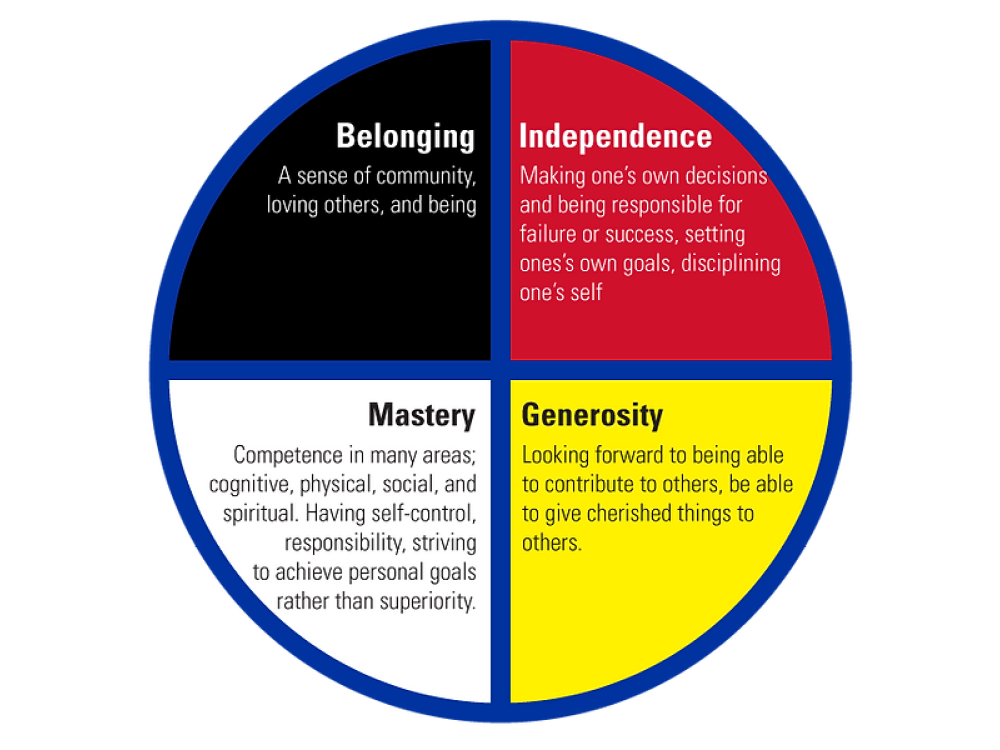

“I always graduated to more and more substances,” Abel says. “I thought I was cool. I was like, ‘finally I found my people. I belong somewhere, like this is it,’ but it really wasn’t. I was an outsider trying to fit in. I always felt like that.”

Crime

Abel found himself living among people deeply involved in drugs, and soon he was drawn into the business. He befriended a dealer and started selling drugs. He went on “missions” that, in hindsight, felt reckless. “I’m so naïve at this point,” he says. “But I was so down to do anything for validation.”

Before long, Abel was selling on the street. “I learned how to walk the walk, talk the talk, until it became real. Until it became too real, actually.”

The environment around him was violent and harsh. “It made me into a different person. That person back then wouldn’t sit here and talk to you about anything. I was very aggressive, very defensive. A lot of that was fear. I was scared, so I had to be tough,” he says.

At the same time, Abel was using the drugs he was selling. His addiction deepened. He recalls how, at his lowest, he stopped seeing people as human. He witnessed things that no longer shocked him. “That’s why people keep using it, because we’re trying to forget all that,” he says.

Everything worsened when he started using crack, a chemically processed form of cocaine that is known to be more addictive. “It devastated me. And I didn’t even notice until it was too late,” Abel recalls. “I couldn’t even smoke weed anymore. I didn’t want to do any other drugs. All I wanted was to use. Nothing else mattered.”

Recovery

Things changed for Abel after he was evicted and moved into a “traphouse,” a house where people were constantly using and selling drugs. It was there he tried to quit for the first time. “The people around me were all actual addicts, just like me … I just didn’t want to end up like the guys I was living with.”

A turning point came when Abel saw a friend post online about his own sober journey. “That kind of kickstarted it all. Seeing that there was hope,” Abel recalls. His friend helped him sign up for Alberta Works and referred him to the Calgary John Howard Society.

Recovery was not easy. “I started going to meetings while still living in a traphouse where people are still [using drugs]. Trying to quit while being in an environment like that, it makes it so hard.”

Abel’s challenges are common: long delays for treatment, unstable housing, and the absence of supportive networks all increase the risk of relapse. Recovery isn’t just about abstaining from drugs. It requires safe housing, strong supports, and access to programs.5

Eventually, Abel was paired with Marcy, a CJHS support worker. She helped him access housing and treatment and stayed by him through many ups and downs. “It was kind of upsetting for me, having her see me at my lowest,” says Abel. “She’s really stuck a leg out for me and continues to support me, even though I was going through a lot and didn’t even know which way was up.”

For Marcy, the distinction was clear. “I’ve seen both sides of him. I know that’s the addict, it’s not the actual person,” she says.

Abel’s lowest point came when he was homeless and moved in with his biological mother, who he hadn’t lived with since childhood. “When I was with my mom, I didn’t really talk to Marcy or anyone that much … I started breaking those connections very quickly.” Without stable housing and social supports, relapse followed.

Still, Marcy was there, waiting until Abel was ready to try again. Eventually he reached out, and she drove him to detox. “Detox really helped me have that clarity for the first time in a long time … it gave me that brief taste of my real personality,” says Abel.

This time, it stuck.

Sobriety

This past August, Abel celebrated one year sober.

“Finally now I have a year sober and I’m taking my medication for anxiety and depression, and ADHD, and things are going quite well for me. I have a nice place, I got a new job. I’m doing quite good.”

Abel asked Marcy to introduce him at his one year sober ceremony. “It has been so rewarding seeing the changes in him as he grows,” says Marcy. “He’s done all the hard work. I’ve just kind of held his hand along the way.”

Still, Abel admits it takes constant effort.

“It kind of feels like when you’re on a treadmill and you don’t want to keep going, but the treadmill’s still going so you’ve got to keep walking. That’s kind of how life feels right now … it gets tiring, but I’d rather be here than where I was.”

Through CJHS and his own determination, Abel has built stability: housing, work, and healthier routines. “Even those little things, like taking time to go see a doctor and making appointments. I’m trying to build some kind of stability in my life.”

What has made the difference is having someone in his corner. “I felt like I had an extra pillar of support that I could go to if I needed help or just someone to talk to and ground me.”

Today, Abel recognizes sobriety is a choice he must make every day. “I’m stable. I’m comfortable. I’m safe. I’m still figuring out who I am. I’m doing it sober now and I don’t know where I’d be if I didn’t get help and reach out. I’d probably be dead, homeless, or in jail.”

Abel leans back and groans when you ask him what advice he’d give other people going through similar things. Almost embarrassed, he answers. “If you want help and you know you want the help, it’s out there. But you’ve got to be willing to go get it. That’s the scary part. It was the hardest part for me asking for help, but once you do, it gets easier.”