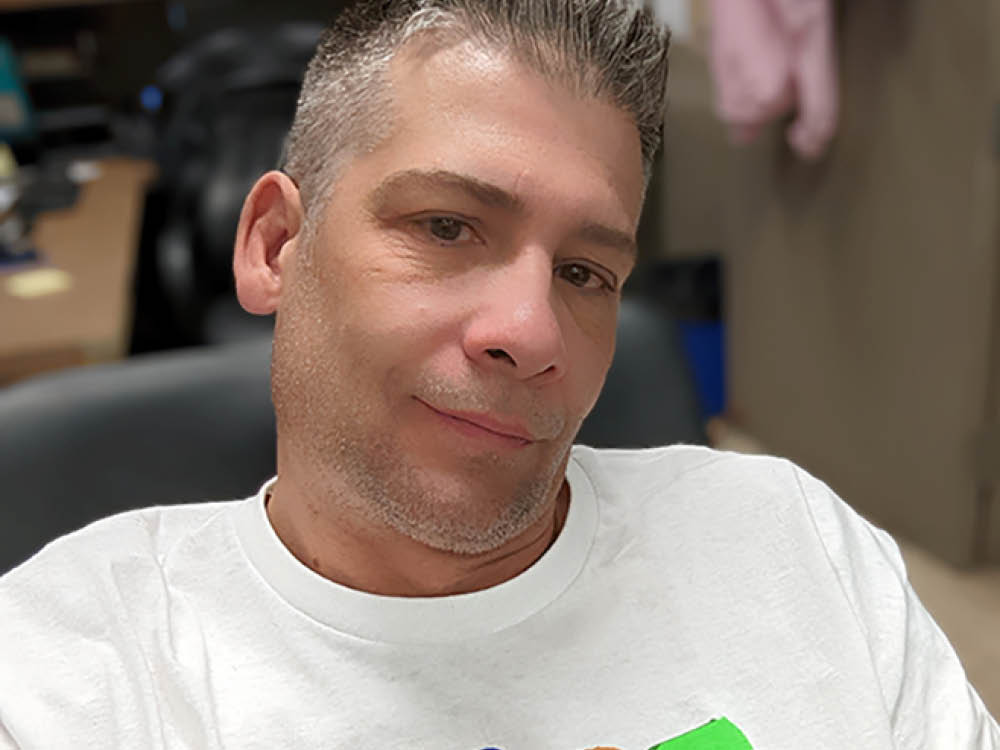

It wasn’t long ago that Michael was battling his own addictions. Now, thanks in part to the home he found through one of CJHS’s housing programs, he’s able to use his lived experience to help others as a support and outreach worker.

Michael’s childhood was unstable — he and his twin brother were removed from their mother’s care multiple times by the age of 6. They spent a decade in foster care.

“Being Native and growing up in foster care, there’s always that element of racism,” he says. “I was always on the fringe of things and never felt like I belonged.”

When Michael was 18, he broke his back in a logging accident. He began to use alcohol to help with the pain. “I didn’t know where I was going or what I was going to do because I always pictured myself working in the bush for the rest of my life. But I guess life had other plans.”

Michael and his brother decided to head to Maskwacis (formerly known as Hobbema), where their birthmother was living.

“We felt out of place there, too,” he remembers. “The way we grew up was so different from the lifestyle on the reserve. There was so much violence, drugs and alcohol. It was really scary so we didn’t stay long.”

At this point, Michael was in the throes of addiction. He moved back to Calgary where he experienced homelessness on and off for eight years until his liver failed. He quit drinking but, when he couldn’t find a job, he fell back into the cycle. This time, it was using drugs and selling them to pay for his addiction.

Then his brother passed. “Grief was so deep,” Michael says. “I became angry, isolated and very hostile towards people.”

Michael was first arrested in 2009. “My second time in the pen, I was like, what am I doing?” He says. “This really is just a waste of life, living in a cage.”

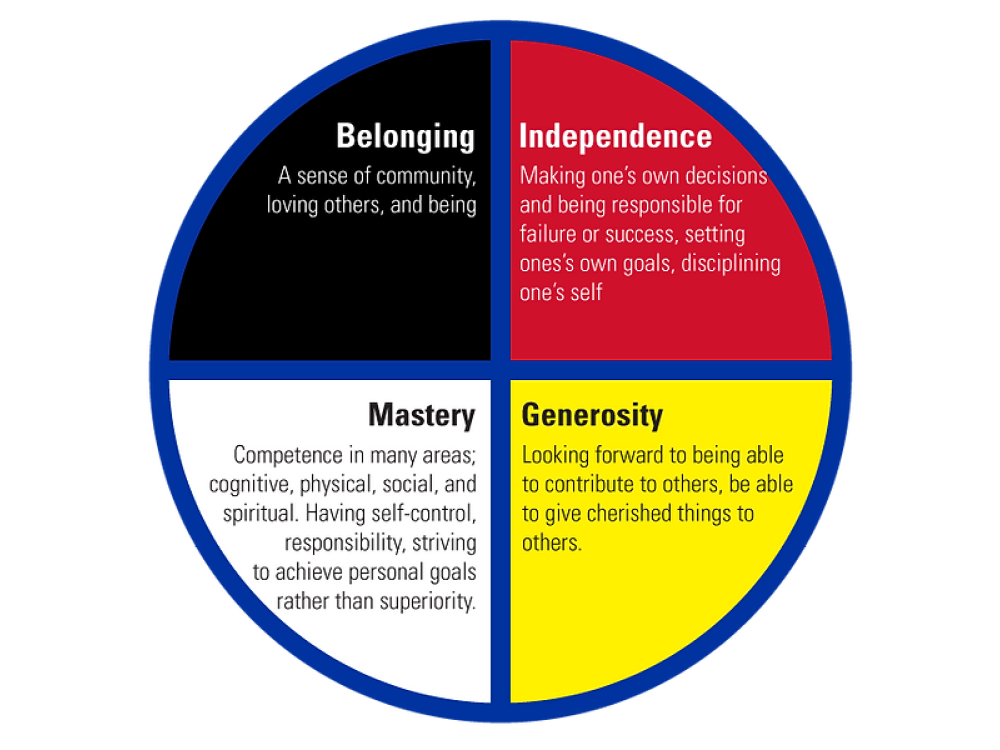

In prison, Michael began participating in an Indigenous cultural reconnection program. “I made a connection to the higher powers and it gave me what I needed to change,” he says. “I started developing ideas about being healthy and living differently.”

Michael had some ups and downs after his release but was able to connect with the Adult Housing Reintegration Program at CJHS. “That was a turning point,” he says. He’s now been housed for over four years — allowing him to maintain the outreach job where he uses his newfound spirituality to help others.

“It’s really essential to my recovery,” he says. “Praying in prison changed something within me that gave me a deep desire to help others.”

Michael says that he would not be where he is today if key people didn’t take a chance on him, whether it was landlords, support workers or employers. “We need people to take that chance on us. People say you need to see to believe but, the truth is, you need to believe in order to see,” he says. “People believed in me and now they’re seeing.”