A literacy guru’s uneasy learning journey

Academically, I was a mediocre student throughout secondary school. Most times, my mind wandered during classes. Teachers passed over me and didn’t express high academic hopes for me. Consequently, I went through school thinking I was an inadequate student.

I didn’t believe in my academic potential until university, and it was thanks to a fellow classmate whose confidence in my capabilities sparked that belief and filled the so-called “holes.” I now consider my mediocrity and wandering mind as masks hiding strengths that weren’t nurtured in a system favouring a certain type of learner and learning behaviour.

I wish I could say that I didn’t need another person to enter my life to redirect my educational path. That’s not how my story goes, however. The support of another member of my community enabled me to identify my values and strengths. Once I accepted them myself, I succeeded as a learner on my own terms and completed university with more confidence, clarity, and fresh perspective than I had ever had.

I don’t claim to have the same educational experience as the adult learners at Calgary John Howard Society (CJHS). What I do relate to is their feelings of inadequacy and marginalization in an educational system that didn’t pay attention to them or had no idea what to do with them.

In 2019, approximately 50% of the over 400 adult learners enrolled in the CJHS Literacy and Learning Program reported that they had some high school education. Nearly 20% said that they completed levels somewhere between grades 1 and 9. A few learners declined to answer or reported not remembering their grade completion level.

These statistics don’t fall far from the national average of 75% of offenders in the Canadian prison system who don’t have a high school diploma or equivalency.

Alongside these numbers, we must consider personal anecdotes of educational isolation. When asked about their school experiences, CJHS adult learners often describe “getting pushed through the system” despite being unprepared or “being moved from school to school” for behavioural issues. Adverse childhood experiences in the home also create obstacles to learning. According to some CJHS learners, the trauma they experienced as children “shut their brains down” as young students and seriously impeded their ability to learn. Often, these stories end with school dropout and a path towards criminal activity.

Combined, these numbers and stories highlight “gaps” – what is lacking in an individual’s education history and what, as a community, we seem unable to do with missing pieces. Often, the “gaps” are painful reminders that CJHS learners were overlooked in a school system focusing on those who behaved according to rules and expectations. And they remind us of the few choices they had as young learners.

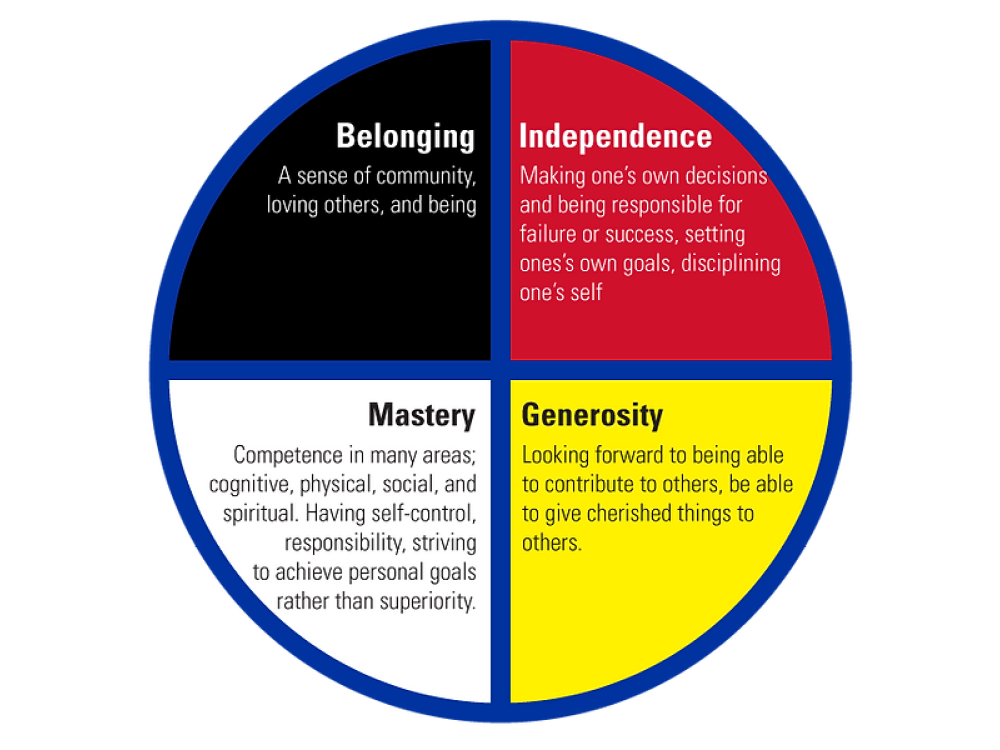

Just like the kind and compassionate classmate who supported my educational pursuits, reintegration support in education for adults with criminal-justice involvement should include programming and people that encourage digging into “gaps” and “inadequacies” to unearth strengths and values.

Additionally, these adult learners would benefit from free options for returning to school to obtain high school equivalencies or achievements. They were robbed of an education as young learners. It seems fair to give them the opportunity to learn what they should have learned freely years ago.

A completed high school education is a foundation for basic needs, sustainable employment, and further learning. With it, learners who have a history of criminal activity have a fair chance at rebuilding their lives and keeping themselves and others safe in our community.

Filomena is the Literacy Coordinator at CJHS.

BY THE NUMBERS

75%

of people in Canada’s prisons don’t have a high school diploma

50%

of CJHS Literacy participants have some high school education

20%

have completed somewhere between grades 1-9

74%

regularly use skills they learned in the CJHS Literacy program